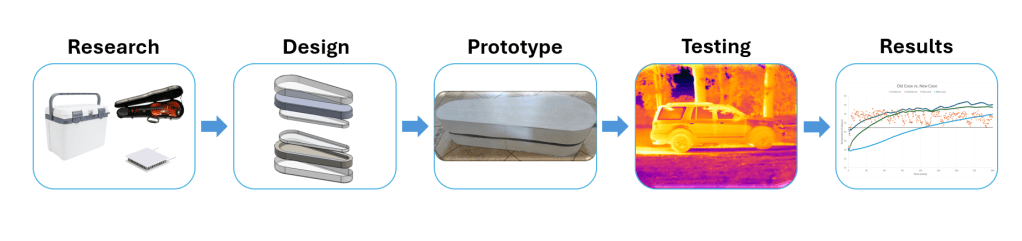

Project Scope

The flowchart above shows the main stages in chronological order of the project.

Intro

Identifying a flaw with existing instrument cases, I embarked on designing a new case that would effectively shield instruments from external temperature conditions using thermal technologies. My research led me to explore various insulation and cooling methods eventually narrowing down to my final design.

Research

I began my research by studying the three main forms of heat transfer: conduction, convection, and radiation. Since an instrument case is typically sealed with no direct airflow between the interior and exterior parts of the case, convection was not the primary concern of heat transfer. Instead, conduction—where heat transfers directly through the case material—was the main challenge, as heat would flow from the exterior of the case into the interior. Radiation was the next factor I needed to consider, as exposure to the sun inside a car, or radiation from surrounding objects, would accelerate heat transfer into the case.

Next, I explored the two main cooling methods for the case: passive and active. Active cooling, which requires an energy source, would increase both the size and weight of the case, making it impractical for this application. In contrast, passive cooling, which doesn’t require an energy source, allowed for a more practical size and design, making it the better option for the case.

I then researched various materials used in passive cooling systems, such as those found in drink coolers and containers for thermally sensitive products. From this, I narrowed my choices down to polyurethane foam and phase-change waxes. Polyurethane foam is widely used as an insulator for containers, while phase-change waxes are commonly employed for thermal energy storage. Ultimately, I chose polyurethane foam due to its ease of installation and low thermal conductivity, making it an effective solution against conduction.

After addressing conduction, I shifted my focus to radiation. After researching different reflective methods to reduce heat absorption, I decided to add a thermally reflective layer to the exterior of the case. This addition would significantly reduce the amount of heat absorbed through radiation, further improving the case’s overall thermal protection.

Design

With my research complete, I moved onto the design phase. Standard violin cases typically have an ovular shape, so I incorporated this into my design to add complexity. Next, I considered the amount of insulation that should be integrated, aiming to balance thermal performance with weight and size to maintain practicality. After examining other products that use polyurethane insulation, I determined that 2 inches of insulation would offer good thermal performance while still maintaining an acceptable weight and size. With these applications in mind, I used CAD software to design the case, adding all the necessary dimensions and specifications. Once the design was finalized, I proceeded to the prototyping stage.

Prototyping

The complex design of my case required forming plastic into a specific shape. To achieve this, I explored various methods for constructing the prototype and ultimately chose the thermoforming process. Thermoforming involves softening plastic and shaping it into a molded form. This approach required me to build an apparatus that included an oven, vacuum, mold, and frame. I constructed each component using woodworking and welding techniques.

Once the thermoforming apparatus was complete, I began creating the prototype. I started by softening the plastic in the oven while it was clamped onto a frame. After the plastic softened, I quickly transferred it to the mold and activated the vacuum. The vacuum pulled the softened plastic down onto the mold, allowing it to take the shape of the case as it cooled and solidified. I repeated this process several times until I successfully formed the inner shells of the case.

However, the thermoforming process was unsuitable for the outer shells, as they required covering a larger surface area, which made forming them more challenging. For the outer shells, I cut a band of plastic and used a heat gun to bend it into the perimeter shape of the mold. I then cut the face of the outer shell and glued it to the formed band.

After forming both the inner and outer shells, I created two halves of the case, each consisting of an inner and outer shell. The inner shell was positioned inside the outer shell, leaving a 2-inch gap between them for insulation. I then applied the foam insulation, layering it until the entire space between the shells was filled. Once both halves were complete, I applied a protective seal around the perimeter and joined the two halves together, completing the final prototype.

Testing

After completing the prototype, I conducted a series of tests to evaluate its thermal performance by placing the case inside a car and monitoring its internal temperature. To compare, I placed both my thermally protective case and a standard commercially available violin case in the car, with thermocouples connected inside each case, as well as one in the car’s interior and another outside. I performed these tests on days when the outside temperature was 95 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, recording the data for a duration of four hours.

Results

After collecting the data from my tests, I analyzed the results, which revealed that the thermally protective case extended the time a case could be safely left in a car by 400% compared to a standard violin case. This demonstrated that my design effectively slows the rate of heat transfer from the external environment into the case’s interior, significantly enhancing its thermal protection.

Conclusion

I successfully designed and prototyped an instrument case that effectively protects instruments from damage in extreme temperature conditions. Realizing the potential of my design, I filed a provisional patent with the United States Patent Office and am exploring opportunities to bring this design to market. This project not only allowed me to achieve my goal, but also helped me grow as an engineer and musician. I’m incredibly proud of the outcome, and hope that one day my design will benefit the music community, helping others who, like me, have faced the challenge of safeguarding instruments under extreme temperatures.